In 2024, ChatGPT alone allegedly produced around 1/1000 of all words produced by humanity each day (Altman, 2024). Now, around 40% of text on active web pages originates from AI-generated sources (Spenneman, 2025). Certain voices still claim that Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is just round the corner, and that scaling up transformers will lead us there. This is the quasi-religious doctrine that has emerged from Silicon Valley.

Given the scale of the output of these systems and the impact of their developers on the global economy (WSJ), it is worth probing whether the claim that scaling transformers will in fact lead to AGI.

This is the third of three linked articles:

- This is no AI bubble – here’s why

- Why we have the AI we do

- The uncomfortable truth about AGI hype

Henri Rousseau, 1905. Le lion, ayant faim, se jette sur l’antilope. Oil on canvas. Fondation Beyeler

The assumption that AGI is achievable through the current technological paradigm (transformers + scale) rests on the empirical observation that there are predictable performance gains to be made with scale (Kaplan et al., 2020). OpenAI’s manifesto has become dogma, extrapolated beyond its empirical basis into a trillion dollar bet that intelligence will in fact emerge from scale.

Indeed, LLMs have demonstrated surprising capabilities that emerged with scale – emergent phenomena such as coding, for which they were not explicitly trained, zero shot learning (where models can complete a task that they have never seen before, without examples), in context learning (where models learn from examples), chain of thought (where prompting a model to mimic reasoning steps improves performance).

These phenomena were exciting because they were ‘out of distribution’ – seemingly novel behaviours and learning not part of how they were trained, glimmers of novel behaviour and learning – a crucial component of whatever ‘AGI’ is (Bubeck et al., 2023). The scaling paradigm is empirically driven, operating under the assumption that scaling first will lead to more sophisticated and ‘general’ emergent abilities later, without a clear understanding of exactly how this works.

As Karen Hao points out, there is no clear definition of AGI – it is variously defined according to the audience. To paraphrase – for consumers, AGI is something out of Spike Jones’ ‘Her’, a seamless (seductive) operating system in your life. When talking with Congress, AGI is a mythical system that will solve climate change and cure cancer. When talking to Microsoft, AGI is an AI system that will generate $100 billion in revenue, and officially on OpenAI’s website AGI is a highly autonomous system that outperforms humans in most economically valuable work – a labour automating definition (Minhaj, 2025).

You have to make a bit of a leap to understand how the scaling manifesto links to AGI. The assumption is made that downstream ‘performance’ (lower loss on a held-out test set – meaning better prediction of the next word in a sentence) corresponds to intelligence, or at least that intelligence will emerge as loss is driven down with more scale.

The connection between prediction and intelligence has substantial theoretical precedent (Hutter, 2005; Solomonoff, 1964; Li & Vitányi, 2019). This is the computational view of intelligence, where intelligence is characterised as compression – the more a system can compress data, the more of its underlying structure it has uncovered; the more structure it has uncovered, the more it ‘understands’. Prediction and compression become interchangeable – a model that can best predict the next token has also found the best, or most general, representation of the underlying structure in the data.

This theoretical link is what makes it plausible at all that lowering predictive loss is a proxy for increasing intelligence. The assumption is that whatever mechanism which allows LLMs to acquire linguistic fluency can, with sufficient scale, reproduce intelligence itself, based on extrapolating Kaplan’s curves and hoping for more emergent behaviours. This rests on the idea that structure and meaning do in fact emerge from distributional learning over text.

The striking success of LLMs in gaining apparent linguistic fluency has led to increasing popularity of a distributional theory of language and language learning. Christopher Manning is one scholar to commit to this idea seriously. He himself does not predict imminent AGI (Manning, 2024) and explicitly recognises that models lack agency, grounding and perception, calling the claim of AGI by 2030 as ‘laughable’. However he does adopt the view that self-supervised learning on linguistic input captures much if not all of the structural regularity of natural language.

Distributions

Distributionalism posits that language can be fully characterised and learned by the statistical patterns of cooccurrence of words, famously articulated by Firth – ‘you shall know the meaning of a word by the company it keeps’. Chomsky famously rejected this position in the twentieth century, arguing that language on its own does not contain enough information to specify the grammatical system children acquire – many distinctions children easily master seemed not to have a clear statistical signature in the data available to them.

In its strongest form, distributionalism is also a rejection of functionalist and usage-based views of language acquisition – there is no need for joint attention between child and caregiver, no role for communicative intent as the pressure guiding learning and meaning. Linguistic competence in this framework arises from tracking the co-occurrence statistics in ambient language alone – children become ‘self-supervised’ learners, according to Manning (Weil, 2023).

The logic of this framework – that surface distributions are sufficiently informative for a sufficiently large self-supervised learner to internalise linguistic structure – provides the only plausible mechanism that AGI optimists can appeal to. Except this mechanism is universalised – if text prediction yields genuine linguistic competence, then prediction over other or combined data streams might yield intelligence.

The difference is in scope, not in kind. Manning’s view is concerned with a single cognitive faculty, while the AGI scaling thesis is that same hypothesis with domain boundaries and epistemic caution stripped away. The core idea remains consistent, that compression through prediction uncovers structure, and the same statistical learning principles that support language acquisition may, in principle, support general intelligence.

The wager

This view of language carries a fundamental wager; that language can in fact be characterised by the distribution of its tokens. In other words, that text alone contains enough information to construct the generative and interpretative processes that produced it. This rests on the idea that prediction and understanding are in some sense equivalent – language is only co-occurrence statistics, and that constitutes the structure and meaning of language.

This means that next-token prediction is not a crude proxy but rather a viable mechanism for extracting the full richness of linguistic structure. Bender et al. (2021) argue that LLMs are merely brittle statistical engines performing high-fidelity mimicry – ‘stochastic parrots’ – regurgitating statistically probable continuations without true understanding. This contrasts sharply with the distributional view, where high-fidelity mimicry is itself the mechanism for uncovering and internalising the underlying structure of language, since language is itself a distributional object; meaning, syntax, pragmatic structure are all encoded in usage patterns, and usage is encoded in text.

Lions

Bender appeals to Wittgenstein to explain why LLMs are not actually using language (Weil, 2023). For Wittgenstein, language gains meaning not from statistical patterns but from participations in forms of life – shared practices where words have consequences, assertions can be wrong, and promises must be kept. ‘If a lion could speak, we could not understand him’ – understanding requires not just linguistic facility, but also participation in a shared form of life; overlapping practices, needs, reactions, perceptions, and ways of going on (Biletzki & Matar, 2023). A lion’s form of life – its hunting practices, sensory world, social relations, and environment – differs so fundamentally from ours that its ‘speech’ would not map onto human meanings.

Henri Rousseau, 1897. La Bohémienne endormie. Oil on canvas. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

LLMs exist outside of normative structures of commitment that, for Wittgenstein, give language its meaning. They cannot lie, as lying requires the capacity for truth, cannot promise since promising requires accountability. They reproduce linguistic forms while being structurally excluded from the practices that give those forms meaning. The distributional view must either reject Wittgenstein entirely, arguing that meaning does reduce to co-occurrence patterns, or accept that what LLMs acquire is not linguistic competence in a meaningfully recognisable sense.

A distributionalist could however maintain that meaning is fundamentally normative and inferential, but that this is not tied to conscious experience or moral accountability. Participation in a linguistic community does not require a human inner life, but only occupying the right inferential roles within a network of communicative practices. It doesn’t matter that LLMs are lion-like, since understanding and meaning can be derived from structural integration into social-linguistic norms.

Algorithmic Information Theory

The good thing about distributionalism is that it can be very cleanly examined with algorithmic information theory – specifically, what it means to learn from text alone, setting aside (for now) philosophical questions on meaning. If we take seriously the distributional view that linguistic competence arises from tracking patterns in text, then algorithmic information theory allows to ask: even if we achieve perfect prediction on text, what have we actually recovered?

Algorithmic complexity theory tells us that distributions over text are degenerate: many distinct causal systems can produce the same surface patterns. The mapping from distribution to generator is fundamentally ‘non-injective’ – there is no unique inverse. Countless incompatible generators can yield identical textual outputs.

Take the text of Hamlet for example. Shakespeare could have written it, someone could have copied it out word for word, or there could be an incredibly lucky room of monkeys with typewriters – all can produce the exact same text distribution with wildly different generators. The ‘inversion problem’ – recovering a generator from its outputs – is, in general, ill-posed. For any real-world text corpus, infinitely many incompatible generators are consistent with it.

Marginal image from Splendor Solis, circa 1582.

We can formalise this limitation using Kolmogorov complexity. Kolmogorov complexity is a way of analysing the complexity of an algorithm. The insight is to view complexity as description length – what is the shortest way I can describe something. Something that can be described more shortly is less complex than one that takes longer to completely describe.

Let G represent a cognitive/agentive generator – the full causal, embodied system that produces text. Let T represent the text output of that generator.

K(G) = the shortest program that specifies the generator

K(T) = the shortest program that outputs the text

While K(T) ≤ K(G) + O(1), the converse does not hold. The generator’s complexity can be arbitrarily larger than the text’s complexity – extremely complex generators can emit very simple signals. When K(G) >> K(T), the mapping is lossy in a fundamental sense – no amount of data or compute can recover information that isn’t there.

The algorithmic data processing inequality demonstrates this precisely. The information about G retrievable from T is upper bounded by K(T). Human linguistic output is a tiny-capacity channel, roughly 30-60 bits per second, compressing millions of bits per second of perceptual and cognitive activity. Furthermore, many cognitive states have identical linguistic realisations (e.g. ‘that’s fine!’), hence degeneracy, and therefore non-injectivity, apply.

Even Solomonoff induction – the theoretical ideal of Bayesian inference – cannot invert such a lossy mapping (indeed any lossy mapping). Because of this, perfect prediction yields a generator that produces the same outputs, not necessarily the same underlying processes. Even perfect prediction cannot invert a lossy mapping – and transformers are much weaker than Solomonoff Induction.

Priors

This seems troubling for distributionalism – if text is degenerate and lossy, then learning from text alone cannot recover the true generator, even in principle. But this may not matter empirically, due to priors. In practice, we do not explore the full hypothesis of all generators compatible with Hamlet. Some generators are adjacent to Shakespeare, others (the monkeys smashing keys) are astronomically distant. Priors determine which region of this space we actually converge on.

This is why distributional approaches’ rejection of much of theoretical linguistics is so interesting. Both generativism and usage-based approaches present inductive biases (priors) to explain how children acquire language. Generativists say its biology, usage-based theorists say its social/pragmatic cues and environmental structuring.

But in a distributionalist position, the only inductive priors are those imposed by the architecture of the model, the training process, and the data itself, if you commit fully to the idea that LLMs actually possess some kind of linguistic competence. This is the essential outcome of the above – since text is degenerate, these priors do almost all the heavy lifting. They determine which generators are reachable, and therefore what kind of ‘competence’ the model can acquire.

Given that text is too impoverished to uniquely specify the generator that produced it, then predicting text – even perfectly – does not automatically yield a system capable of reasoning, abstraction, or systematicity. These capacities are intuitively central to intelligent behaviour; the ability to apply rules, manipulate symbols, generalise systematically, and solve novel tasks.

The question is then – where do the priors of LLMs converge on in the hypothesis space? What kinds of ‘cognitive behaviours’ do these priors actually support?

Shift Ciphers

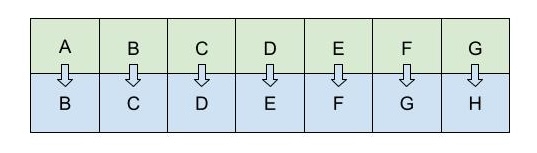

Shift ciphers provide a clean empirical test of LLM reasoning. They are a classic example of a deterministic symbolic reasoning task. A shift cipher, also known as a Caesar cipher (apparently his favourite was ‘3’) replaces each letter in a string by another letter a fixed distance away in the alphabet – so ‘chicken’ becomes ‘bghbjdm’ under a shift cipher of minus one.

Illustration of a +1 shift cipher

Prabhakar, Griffiths and McCoy (2024) systematically study how recent LLMs perform on shift cipher decoding under chain-of-thought prompting. Consistent with previous findings (McCoy et al., 2023), they found that there was a large spike in performance at shift cipher 13, shift 1, shift 3, and shift 23. The LLMs performed incredibly poorly on the rest of the shifts.

This seemingly bizarre pattern is explained by the frequency of these shift ciphers on the internet. ROT-13 is a common shift cipher used in forums, and 1, 3 and shift cipher 23 (which is just shifting -3) are also commonly used to illustrate how shift ciphers work. This indicates memorisation over development of a true algorithm to decode any shift – the models perform well where the internet contains many exemplars, and fails where examples are rare.

Perhaps most remarkably, the probability of the unscrambled output under the model’s pre-training distribution has a strong effect on accuracy. When the unscrambled text is unusual or low-likelihood, performance deteriorates sharply – even when the shift itself is one the model otherwise handles well.

This is somewhat alien to human reasoning – the difficulty of unscrambling a plus 3 shift cipher doesn’t intuitively depend on whether the outcome word is ‘hello’ or ‘hippo’.

The effect also appears to be tied to surface presentation. When given an isomorphic task using numbers instead of letters (shift each number by x in a sequence) GPT-4 achieved near-perfect accuracy. The algorithm is identical with different input domains, and this difference is enough to produce radically different behaviour.

Taken together, these findings indicate these models are profoundly shaped by the teleology of next token prediction. Strong performance on selected instances doesn’t necessarily imply the presence of systematic, domain-general reasoning – rather, it may reflect statistical mimicry tuned to the regions of space well-represented in training data.

SuperARC

The shift cipher failures show that even for a fully deterministic algorithmic task, scaling does not always yield generalisation beyond familiar patterns. SuperARC is a benchmark explicitly designed to test whether next-token prediction is enough to solve toy algorithmic problems, which require abstraction, structure discovery and reasoning (Hernández-Esponisa et al., 2025).

SuperARC explicitly frames intelligence not simply as statistical interpolation or pattern matching, but as the ability to build compact, recursive generative models that can explain observed data. The benchmark presents inverse problems – given a sequence of observations (e.g. binary or integer sequences), can a model infer a minimal recursive program (a ‘generator’) that produces them?

The scoring method emphasises recursive compression and predictive generalisation over statistical compression. Recursive compression is used to see how succinctly the inferred program describes the data, echoing Kolmogorov complexity rather than Shannon entropy (a measure of statistical compression). Predictive generalisation then measures how well the inferred generator continues the sequence. By design, the benchmark makes it difficult to succeed through brute-force statistical compression.

They find that state-of-the-art LLMs perform very poorly, often producing trivial ‘print’ solutions (literally printing out the observed sequences) or ordinal mappings. Both are strategies that avoid constructing an actual generative mechanism. Newer models also did not reliably improve on earlier ones, and where there were gains, these stemmed largely from exposure to more training data – not from emergent reasoning or structural innovation.

Models achieving perfect next-token prediction struggled with genuine model synthesis – creation of a generative program, not just pattern continuation. The inability of LLMs to infer compact generators indicates that their architectural and data-driven priors may not sufficiently bias them towards abstraction or causal modelling, instead favouring memorisation, superficial similarity and statistical plausibility.

Lion. Spanish, after 1200. Met Cloisters.

Brittleness

Brittleness is a well-documented phenomenon in LLMs (Gu et al., 2023; Mizrahi et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2021; Pezeshkpour & Hruschka, 2024; Alzahrani et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2021). It refers to how their behaviour degrades dramatically under minor perturbations that preserve the semantics of the prompt – reordering, paraphrasing, or introducing typos can lead to very different outputs even when the underlying meaning is unchanged.

Haller et al. (2025) examine whether LLMs’ internal representations of truth are stable under out-of-distribution (OOD) perturbations. Using probes to inspect the internal activations of LLMs, and applying surface-preserving perturbations (typos, paraphrasing, reformulations) to push them out of the distribution of what the model had seen during pretraining, they measured how well truth vs. falsity separability held up under said perturbations.

Their results show that the robustness of LLMs’ internal knowledge representations is tightly coupled to superficial resemblance to pre-training data. Truthfulness separability – the ability to decode true vs. false statements from internal activations – degrades as samples become increasingly OOD, across all probing techniques and regardless of model or dataset.

Interestingly, the degree of brittleness also varies by domain – topics like marketing or sociology appeared less fragile to distribution shifts compared with domains like historical fact. This variation in topic robustness cannot be explained by representation frequency in the pre-training data, implying that simply scaling up pre-training corpora may be insufficient for encoding robust, generalisable knowledge.

This is particularly concerning. Because truth representations collapse under perturbation, LLMs may struggle to generalise factual knowledge to novel formulations. This indicates that truthfulness in LLMs is tightly coupled to surface patterns that correlate with truth in the training data.

Brittleness is a diagnostic of a shallow generator – once the surface form drifts off-manifold, the internal scaffolding collapses, undermining the expectation that large-scale self-supervision reliably uncovers deep cognitive, normative, epistemological or ontological structure.

Compression vs. Meaning

Shani et al. (2025) develop an information-theoretic framework to compare how humans and LLMs compress representations of the world. Human conceptual categories such as ‘bird’ strike a balance between compression of diverse examples (robins, penguins, ostriches) while still preserving fine-grained distinctions (some birds can’t fly, some migrate, others are predators). The cognitive system tolerates redundancy and statistical inefficiency in order to maintain semantic nuance.

The authors investigate whether internal LLM representations exhibit the same tradeoff. They find that (in line with extensive previous work) LLM embeddings do form broad conceptual clusters, roughly aligned with human coarse-level categories. This is one of the most striking findings of large-scale compression of text – in the course of minimising prediction error, models learn representations that organise around semantic regularities.

However, LLMs struggle with fine-grained semantic distinctions. Using their information-theoretic metrics, Shani et al. show that LLMs often achieve more optimal compression than humans. But this ‘optimality’ stems from aggressive statistical compression, collapsing distinctions that humans retain. LLMs inductive priorities push them toward a representational parsimony, while humans accept surface inefficiency.

A natural interpretation of this human redundancy is that humans optimise for communicative robustness under uncertainty (the classic analysis of language as a signal in a noisy channel). Listeners may mishear, misunderstand, or lack background knowledge – redundancy helps ensure successful communication. LLMs optimise for compression under a predictive objective – mapping contexts to statistically plausible continuations with minimal loss, rewarding the collapse of any distinction that does not affect next-token probabilities.

From the perspective of algorithmic information theory, this divergence is precisely what we would expect. The compressibility of text alone does not reflect how language operates in this noisy, social channel. Human language is shaped by cooperative pressure (at all levels – from sound to meaning) – the need to disambiguate, anticipate misunderstanding, and preserve information for an interlocutor with different background knowledge.

Next token prediction is a one-directional compression task. It is not optimising for communicative success in real time but for efficiently mapping contexts to statistically plausible continuations. Even if a model achieves maximal compression of the text distribution (loss driven down e.g. with scale), that compression need not preserve the distinctions retained in language for human-like communication.

Model collapse

Model collapse is a phenomenon highlighted by Shumailov et al. (2024). When a generative model is repeatedly trained on its own output (i.e. synthetic data), its performance degrades over generations. Diversity shrinks, probability mass concentrates on fewer sequences, and perplexity worsens over generations. After enough iterations, LLMs eventually spit out nonsensical sequences of characters. Even when initially only a fraction of the training data is synthetic, collapse still occurs over multiple generations (though more slowly).

This indicates that text-only, next-token prediction is lossy. The model cannot recover the full diversity of the original distribution. Overcompression and smoothing inherent in predictive training cause some patterns to disappear. In other words, the priors embedded in the model architecture and training process do not guarantee convergence to genuine linguistic generators, but rather to a restricted, higher-probability subset of the original distribution.

Bear in mind that around 40% of the internet is now synthetic. However Schaeffer et al. (2025) argue that catastrophic runaway collapse is unlikely under realistic training regimes that mix synthetic and human data. Yet even under these moderated conditions, the tail of the distribution (i.e. low probability, rare events) is disproportionately affected – the tail is the first to go.

LLMs’ autophagous nature (literally eating their own tails) has caused significant concern – as synthetic information saturates our ecosystem, less human high-signal data is available to scale.

Whether this will impose a hard ceiling on scaling remains to be seen. But collapse reveals a fundamental limitation that persists regardless of training mixtures: rare, nuanced or low-probability language is structurally vulnerable to irreversible erasure. As Taori and Hashimoto (2023) demonstrate, this kind of attrition falls disproportionately on linguistic minorities and marginalised groups.

Rare language is not less valuable than frequent language. Collapse demonstrates that next-token learning compresses aggressively and irreversibly.

Henri Rousseau, 1891. Surprised! Oil on canvas. National Gallery, London

Escape hatches

There are two obvious objections to the above.

Escape Hatch 1: We don’t need the true generator – just a behaviourally adequate surrogate.

Algorithmic information theory shows you cannot invert the mapping from the generator to text – but why should we want to do this? All you need is some generator in that equivalence class that produces indistinguishable linguistic behaviour – the goal shifts from reconstructing cognition to mimicking the output distribution.

A surrogate generator that behaves like humans on text prefixes sampled from the training distribution is good enough. If you relax the definition of intelligence to ‘behaviourally indistinguishability in language use’, then text could indeed be sufficient in principle.

In doing so you lose:

- Cognitive parsimony

- Causal mechanisms

- Normativity

- Grounding

- Truth

- Generalisation outside the training regime

And you gain:

- Imitation

- Simulation

- Statistical continuation

- Surface-level alignment

- In-distribution competence only (with erratic out-of-distribution behaviour)

This shifts the burden of proof – if behaviour does not uniquely determine cognition, you must explicitly reject cognition as necessary for intelligence. This is not actually incoherent – but is quite a sharp theoretical move, effectively redefining intelligence as performative adequacy under a predictive objective. The project then shifts from building a system with general intelligence to building a system that speaks as though it had general intelligence. This concession lowers the demand but does not eliminate the gap – a large contributor to the failures above is the teleology of the training objective, which is not changed with scale.

Escape hatch 2: The generator we aim to approximate is not cognition – it is only the linguistic submodule

Downsize the target! Instead of treating human linguistic output as the result of a massive, embodied, grounded cognitive system, you assume that the relevant generator is much smaller:

GLanguage << GMind/brain

The goal is not to recover cognition but to recover a freestanding linguistic module – a statistical system encoding grammar, lexicon, and discourse competence. If language is just a large text distribution, then grounding is optional, the linguistic generator becomes tractably small; and text becomes the correct data source for learning it.

Interestingly, this position is simultaneously Chomskian and anti-Chomskian:

- Anti-Chomskian as it denies the need for innate linguistic structure

- Chomskian, because it posits an autonomous linguistic module insulated from wider cognition

What you get is a neatly bounded generator whose complexity is similar to the text distribution itself, making next-token prediction much less lossy and a far more tractable method for reconstructing linguistic competence.

The costs:

- Linguistic competence is separable from cognition

- Meaning does not require grounding – it becomes usage-internal, not world-directed

- Semantics collapses to statistics of occurrence

- Language need not reflect the structure of thought, perception, or embodied experience.

This dissolves the connection between linguistic competence and actual human cognition, treating language as a self-contained statistical object – not a cognitive phenomenon tied to perception and action, but a surface that models itself, not an interface to the world.

Let’s entertain these views!

If text is sufficient, then knowing is behaving correctly in language. This is not a new philosophical position – but it is important to point out that this is what is tied to the AGI project.

Knowledge is defined not by internal world-models but by linguistic performance – to behave as if you know X is to know X.

Thus, if an LLM answers questions about Paris reliably, it ‘knows Paris’; if it solves physics problems, it ‘knows physics’. This is a perfectly coherent behaviourist epistemology, redefining knowledge as competence, meaning as distributional role, and understanding as behavioural adequacy.

Epistemic states collapse into usage patterns, pithily captured by Sam Altman himself:

This is in essence the theoretical move that the scale to AGI narrative has to adopt. Redefine intelligence, such that behavioural surrogates can be said to be intelligent.

As we see above however, even this position is not empirically borne out by LLMs – their bizarre performance on shift ciphers, brittleness, and mismatching output distributions (curtailing low probability sequences) indicate a mismatch in behavioural adequacy – LLMs do not as of yet reliably approximate human behavioural competence across all domains.

Even if we grant that text is enough, and knowledge is equivalent to behavioural competence, we must still accept that transformers do not recover the same generator – they recover a different generator that is merely behaviourally adequate within certain domains. Even if LLMs ‘know’ in the behavioural sense, they do so in a structurally alien way, with different inductive biases, different failure modes, and different epistemic commitments.

Both escape hatches avoid the theoretical obstacles only by downscaling what intelligence is allowed to mean. Either intelligence is behavioural smoothness in dialogue, or intelligence is mastery of language as a sealed-off distributional object. In both cases, intelligence as a general, grounded, embodied, causal, world-model-based, truth-sensitive and norm-sensitive phenomenon is given up. What remains is linguistic simulation.

Philosophy….

When a computational model of an islet of Langahan (a substructure in the pancreas) simulates the production of insulin, somatostatin or glucagon, the simulation remains safely separate from biological function. But the outputs of computational models of language enter human interpretative channels – they escape the lab, and enter the wild. These channels carry our social, political, and epistemic worlds. Work, relationships, information exchange all depend on the interpretability of language for most.

This is why linguistic competence is compelling – the medium is participatory, even if the generator is not. Few call AlphaFold intelligent.

LLMs operate in this normatively frictionless space, consuming vast resources while having no skin in the game. They’re the ultimate expression of what Hannah Arendt called ‘world alienation’ – discourse severed from consequence (Tömmel & d’Entreves, 2025).

Arendt conceives of action as the human capacity to begin something new, to introduce the unexpected into the world. Action is defined by freedom, and plurality. Freedom for Arendt does not mean to choose among a set of alternatives, but rather spontaneity – the ability to act in ways that cannot be predicted from past conditions. This is rooted in ‘natality’ – every birth introduces a singular, irreducible novelty, capable of generating outcomes that are not derivable from existing circumstances. Arendt writes:

‘It is in the nature of beginning that something new is started which cannot be expected from whatever may have happened before…the fact that man is capable of action means that the unexpected can be expected from him, that he is able to perform what is infinitely improbable. And this again is possibly only because each man is unique, so that with each birth something uniquely new comes into the world.’ (Arendt, 1958: 177-8)

How different this conception of humanity is to Altman’s utterly nihilistic one:

‘I am a stochastic parrot and so r u’

Arendt conceptualises freedom as points where individuals step out of routine, private life to create public spaces where freedom can appear. Action is therefore not just behaviour, but also engagement with public consequences that is simultaneously unpredictable, singular, and consequential.

The second defining feature of action is plurality. Action only exists in the presence of others, whose perspectives render deeds meaningful. Words and acts gain significance because they are witnessed, interpreted, and responded to by a plurality of actors. Without plurality, novelty cannot register as meaningful action, and collapses into isolated, private behaviour.

LLMS are trained to suppress novelty. Training objectives reward median behaviour, while punishing deviation from the expected. Reinforcement Learning through Human Feedback (RLHF) is a post-processing step for LLMs which further rewards alignment with the preferred over the unlikely – outputs are optimised for engagement.

This is the opposite of natality – LLMs are optimised to reproduce statistically likely and preferred patterns, precluding the ‘infinitely improbable’ by design. Brittleness under perturbation means that LLM outputs cannot reliably navigate the social contingencies that define meaningful plurality. RLHF further distorts the mapping between output and social action – engagement replaces truthfulness and responsibility, and outputs are tailored to satisfy human preferences, not to act freely in a plural world. The model is incapable of spontaneous or accountable action.

LLMs simulate linguistic behaviour, but lack both natality and plurality. Empirically, this manifests in the disappearance of tails, brittleness to perturbation, and alignment-driven drift. Behavioural adequacy in text does not equate to human-like action, agency or knowledge.

Hyperreal

And so we enter Baudrillard’s hyperreal as our information ecosystem becomes saturated with synthetic content. Hyperreality is where signs displace referents entirely (recall that the distributional paradigm rejects the need for referents completely), creating a ‘real without origin’, a copy of a copy – what Baudrillard calls a ‘simulacrum’ (Baudrillard, 1981).

Baudrillard illustrates the hyperreal with the analogy of the map and the territory. This follows four stages of simulation:

- Reflection: the map reflects the territory (traditional representation)

- Masking: The map obscures the territory (ideology, selective representation)

- Absence: The map substitutes for an absent territory (the territory is gone, but we still pretend it exists)

- Simulacrum: The map precedes the territory (pure simulation, with no original)

When an LLM discusses Paris, or democracy, it is not referring to the real place, or actual political systems, but instead to the distribution of Paris- and democracy- tokens in its training data. LLMs generate exactly such hyperreal discourse; fluent, convincing, yet untethered from truth, action (in the Arendtian sense), or accountability. RLHF amplifies this, optimising for engagement over fidelity, producing outputs that circulate in human channels while remaining ontologically and epistemically utterly alien.

Henri Rousseau, circa 1907. The Repast of the Lion. Oil on Canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A fascinating analysis of language in the House of Commons shows a sharp spike in words and phrases preferred by ChatGPT since its introduction in 2022. Research papers show similar patterns. Each iteration moves us further from what Arendt called the ‘common world’ – the shared reality that makes political action possible – destroying the conditions for genuine beginnings.

Is this intelligent? AGI proponents often pursue LLMs with the explicit hope of generating novelty – solutions to complex problems, unexpected scientific insights, transformative discoveries etc. They seek outputs analogous to Arendtian ‘beginnings’; spontaneous, meaningful, and consequential innovations that could not have been predicted from prior data. The transformer-scale paradigm is structurally at odds with this goal. Apparent novelty is constrained to recombination of existing data – the model cannot introduce consequential beginnings that Arendt describes.

LLMs are optimised to produce outputs that appear creative or surprising, but only within the confines of familiar distributions. This is a hyperreal form of innovation, which is convincing, engaging, and plausible while untethered from causal, social, or epistemic reality. Accepting the sufficiency of text for AGI thus also implicitly accepts that true, actionable novelty in the Arendtian sense cannot occur. The aspiration for AGI is therefore at odds with the track it is on. The features that make LLMs performant – predictive compression, alignment with high-probability sequences, and surface plausibility – simultaneously preclude the genuine unpredictability, responsibility and plurality that define meaningful action.

The key insight might be: businesses don’t need AGI to create value, but they do need to understand what they’re actually buying – neither intelligence nor its simulacrum, but tools that produce compelling statistical completions within familiar manifolds. The companies that understand the boundaries (where brittleness emerges, where model collapse begins, where the generator diverges from reality) will outcompete those chasing the AGI fantasy.

Alzahrani, N., Alyahya, H., Alnumay, Y, AlRashed, S., Alsubaie, S., Almushayqih, Y., Mirza, F., Alotaibi, N., Al-Twairesh, N., Alowisheq, A., Saiful Bari, M., Khan, H. (2024). When Benchmarks are Targets: Revealing the Sensitivity of Large Language Model Leaderboards. In Lun-Wei Kyn, Andre Martins, and Vivek Srikumar (eds.) Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pp. 13787-13805, Bangkok, Thailand. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Arendt, H. (1958). The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baudrillard, J. (1981). Simulacra and Simulation, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Bender, E., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? In Proceedings of FAcct 2021). Association for Comuting Machinery, New York. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922

Biletzki, A. and Matar, A. (2023). Ludwig Wittgenstein. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/wittgenstein

Bubeck, S., Chandrasekaran, V., Eldan, R., Gehrke, E., Horvitz, E., inter alia (2023). Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4. https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.12712

Gu, J., Zhao, H., Xu, H., Nie, L., Mei, H., and Yin, W. (2023). Robustness of Learning from Task Instructions. In Anna Rogers, in Jordan Boyd-Graber, and Naoaki Okazaki (eds.), Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023, pages 13935–13948, Toronto, Canada, Association for Computational Linguistics.

Haller, P., Ibrahim, M., Kirichenko, P., Sagun, L., Bell, S. (2025). LLM Knowledge is Brittle: Truthfulness Representations Rely on Superficial Resemblance. https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.11905

Hernández-Espinosa, A., Ozelim, L., Abrahão, F. S., and Zenil, H. (2025). SuperARC: An Agnostic Test for Narrow, General, and Super Intelligence Based on the Principles of Recursive Compression and Algorithmic Probability. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.16743

Hutter, M. (2005). Universal Artificial Intelligence: Sequential Decisions Based on Algorithmic Probability. Springer.

Kaplan, J., McCandlish, S., Henighan, T. et al. (2020) Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. arXiv:2001.08361.

https://x.com/sama/status/1756089361609981993

Li, M. & Vitányi, P. (2019). An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and Its Applications. Springer.

McCoy, T., Yao, S., Friedman, D., Hardy, M., and Griffiths, T. (2023). Embers of Autoregression: Understanding Large Language Models Through the Problem They are Trained to Solve. https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.13638

Minhaj (2025). Will AI Take My Job? With Karen Hao. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e70RT6c01M8

Mizrahi, M., Kaplan, G., Malkin, D., Dror, R., Shahaf, D., and Stanovsky, G (2024). State of What Art? A Call for Multi-Prompt LLM Evaluation. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 12:933–949.

Manning (2024). https://x.com/chrmanning/status/1768291975005196326

Pezeshkpour, P. and Hruschka, E. (2024). Large Language Models Sensitivity to The Order of Options in MultipleChoice Questions. In Kevin Duh, Helena Gomez, and Steven Bethard, (eds.) Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2024, pp. 2006–2017, Mexico City, Mexico. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Prabhakar, A., Griffiths, T., McCoy, T. (2024). Deciphering the Factors Influencing the Efficacy of Chain-of-Thought: Probability, Memorization, and Noisy Reasoning. https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.01687

Schaeffer, R., Kazdan, J., Arulandu, A. C., Koyejo, S. (2025). Position: Model Collapse Does Not Mean What You Think. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.03150

Shani, C., Soffer, L., Jurafsky, D., LeCun, Y., Shwartz-Ziv, R. (2025). From Tokens to Thoughts: How LLMs and Humans Trade Compression for Meaning. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.17117

Shumailov, I., Shumaylov, Z., Zhao, Y. et al. (2024). AI models collapse when trained on recursively generated data. Nature 631, pp. 755–759. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07566-y

Solomonoff, R. J. (1964). A formal theory of inductive inference. Part I. Information and Control 7(1) pp. 1-22.

Spenneman (2025). Delving into: the quantification of Ai-generated content on the internet (synthetic data). https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.08755?

Taori, R. and Hashimoto, T. (2023). Data feedback loops: Model-driven amplification of dataset biases. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 33883–33920. PMLR.

Tömmel, T. and d’Entreves, M. P. (2025) Hannah Arendt. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2025 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2025/entries/arendt/

Wang, B., Xu, C., Wang, S., Gan, Z., Cheng, Y., Gao, J., Awadallah, A. H., Li, B. (2021). Adversarial GLUE: A Multi-Task Benchmark for Robustness Evaluation of Language Models. In Thirty-Fifth Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems Datasets and Benchmarks Track (Round 2).

Weil, E. (2023). You are not a parrot. Intelligencer. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/ai-artificial-intelligence-chatbots-emily-m-bender.html?ref=disconnect.blog

Zhao, Z., Wallace, E., Feng, S., Klein, D., Singh, S. (2021). Calibrate Before Use: Improving Few-Shot Performance of Language Models. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 12697-12706. PMLR.

Putzier, K. (2025). How the U.S. Economy became Hooked on AI Spending. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/tech/ai/how-the-u-s-economy-became-hooked-on-ai-spending-4b6bc7ff